- Home

- Christopher Radmann

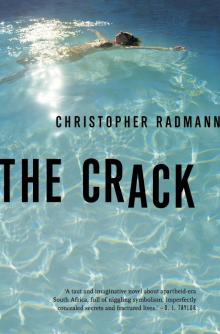

The Crack Page 2

The Crack Read online

Page 2

Today, Solomon was not hers. His stern body with his lithe limbs and shaven head would not be servicing the garden. Grass would not be mown, shrubs trimmed, flower beds weeded nor cracks noticed by Solomon. Solomon would not hum and sing as he worked.

Today was Thursday, and New Year’s Day.

And Hektor-Jan had to disappear. Even on this first day of 1976. His promotion demanded such things of him. No longer would he wear a uniform. Now he was in plain clothes and he was going to have to rely even more on his wife to keep the home fires burning, their little ship on even keel. Janet was left holding the fort and now there was a crack in one of the surrounding walls, a chink in their armour.

Like a giraffe, she lowered her elegant neck to the surface of the water. Her sunglasses stayed perched on the top of her head. Be still, be still, she silently commanded the waves. It would not be long now.

Crouched there, she suddenly sensed, as she sensed the house and surrounding garden – her home, her motherly, wifely, womanly domain – that she was being watched. Just as her short neat dress crept up her slim thighs and exposed the backs of her legs to the sun, Janet felt the prickle of a male gaze. She knew without looking that it was coming from the neighbours to the left. That once again, it was Doug, Douglas van Deventer, and that Noreen was no doubt buried somewhere in the house, possibly incapacitated by one of her migraines, lying in state in her bedroom with the curtains drawn. That would leave Doug free to grasp his shears and a little ladder and edge along the wall that bounded their properties. He would be pruning. Even at this stage of the summer, there would be the snip-snip of wayward branches being cut back, brought under control. And Doug’s head would bob along the boundary. Like a dog at the wall, leaping to look up and over and into their lives. Doug the dog. And if he clambered to the top of that little A-frame ladder, he could peer through the bushes and tangled foliage into their garden, right across the lawn and almost, but not quite, up Janet’s dress.

The backs of Janet’s legs stung in the sun.

Now she was caught between propriety, her own at least, and the urgent need to confirm the existence of the terrible crack that seemed to split the bottom of the pool. In a moment the water would finally be still. If she leaned out a little further, just a fraction further –

Janet did not lean just yet. She sent one hand to the back of her dress and gave it a modest tug. It was high, but hopefully not too high. Her hand came back around. She leaned out as far as she dared and held her breath.

Ma, came the urgent whisper from her eldest. Ma, hissed Shelley.

Janet froze. She could not move. She could not look back now.

He’s at it again, Ma, whispered Shelley and she knew that the children had spotted Desperate Doug amongst the trembling foliage.

It’s Uncle Doug, Pieter’s piping voice confirmed. Like he was proud. Like he was unwrapping yet another Christmas present. Janet closed her eyes. In no way was Doug van Deventer related to them; they were just polite kids.

His older sister shushed him. Not so loud, she hissed.

They all knew Mr Doug van Deventer. Uncle Doug. His strange habits. The way the little man managed to do lots of gardening when Mommy lay in the sun, or when Mommy occasionally swam or when Mommy patrolled the garden checking that Solomon the garden boy had done a good job. Uncle Doug was very friendly, but there were times when he gave them the creeps, when they wished that he was less friendly and that he would stop pretending to cut branches and peering in on their lives. He was a bit like the giant in Jack and the Beanstalk, hey. Even though he was a shorty-pants, a small man, hey. More like Rumpelstiltskin, if you wanted to get all technical.

Janet did not want to get all technical. One did not get technical when one was about to fall into the pool with one’s skirt hitched up almost beyond the bounds of modesty in front of a leering horticulturist and one’s three young offspring. And there was the crack. It was surely about to reveal itself when the tiresome water finally ceased shimmering.

There, there. Now. Almost now. If she waited for just another second or two, leaned out another fraction of an inch, there it would be. She could be sure. Possibly, absolutely certain. Many things in this life are uncertain. Janet wanted at least to be certain of that one thing. It is not often that one discovers a crack in the bottom of the pool on New Year’s Day. She leaned forward another fraction.

Yippee! screamed Pieter as she toppled into the pool.

One moment she was suspended above the water. Then she was a living splash.

Yippee! yelled Pieter and then they were all in the pool, all three of them like puppies or seals, wriggling and thrashing beside her, on top of her, kicking up water in her face and making her gasp and choke. They were laughing. Hanging from her, pulling at her arms and legs. She would lose her dress. She was fighting for breath, then she was laughing too. Clutching them to her like a watery mother hen as they wriggled and squealed like electric eels. Brown worms. They were wriggling worms and she was the early bird.

Marco Polo, Sylvia shouted. The memory of the recent game still fresh and sharp.

Sharky, shrieked Pieter, his recent vomiting forgotten.

Janet threw back her head and laughed.

She wiped her hair that instantly had plastered her face. She swept clear the brown, slick curtain and peeped across the garden before the children renewed their attack. She laughed and laughed as the thick rhododendrons wriggled against the neighbour’s wall and then were still.

Suddenly, she too, was still.

The shock pulsed right through her.

She felt it black and swift and certain. There was no mistake.

It was a mistake.

She went rigid.

She was standing on the crack at the bottom of the pool.

He slept and dreamed and his dreams mocked his sleep. In the heat of his midday bed, he turned and cursed himself. In the house of his father-in-law were many rooms. But not one he could call his own. He did not feel at ease. He felt his children, the fruit of his loins, twisting and turning. It was a long hot night and now it was well past midday. He lay asleep, but waiting. From within the four warm walls of his mind came the Roepstem, came the Call. The voices were urgent and unquiet. He knew what to do. He always knew what to do. He reached under his pillow for his gun. It was at the ready. His knife was hidden, but his gun was always waiting. For who should descend into the deep but him. And with each uncomfortable sigh, he breathed in the certainty. With each breath he blessed the Lord his strength, which taught his hands to war and his fingers to fight. There was the thud of subdued flesh and the slap of recognition. There was the crunch of bone and the silent seeping of blood. Contusions and joint-popping contortions. Internal bleeding and hopeless screaming. But he blessed his God, his goodness and his fortress, his high tower and his deliverer, his shield and he in whom he trusted, who would subdue his people under him. He was fond of the psalms. But out in the darkness the monster began to walk, and the warrior slept. He was terrified.

2mm

The poverty in which most African families lived had far-reaching implications for many children. As a result, the boundaries were not always clear between childhood, adolescence and adulthood. The youth of ‘school-going age’ spent their days on the streets doing odd jobs and playing, but mostly taking responsibility for their siblings and homes while their parents were at work from early morning until late at night. Many had to raise cash for their families as hawkers (selling fruit, peanuts and other goods on trains and at various railway stations) and others worked full time as providers. Child labourers included ‘spanner boys’ who helped to fix cars and those who sold coal and firewood, as Soweto had no electricity.

– Sifiso Mxolisi Ndlovu, The Soweto Uprisings: Counter-memories of June 1976

It is very difficult for me to open up and write about my husband, because it is a pain you can’t describe to anyone else. My husband began to suffer from stress after being exposed on a daily basis to scenes

where people had been killed, shot or maimed – to people whose decomposed remains he had to take out of the water in the course of his job as an emergency diver for the South African Police Service.

It became so bad that he began to patrol the house at night, getting up at the slightest sound and inspecting the entire house and property. Our curtains had to be left open so that he had a clear view when he heard a sound. He sat staring through the window for hours and no one could persuade him to sleep.

– Johan Marais, Time Bomb: A Policeman’s True Story

The crack did not go away. No. It seemed it was there to stay.

When they trooped inside on that first day of the crack, she sensed the burden that she was going to have to carry to her husband. It seemed as though life was a spell so exquisite that something now was trying to break it.

Despite their laughter and the children’s excitement that Mommy had swum in her clothes and had discovered the joys of Marco Polo and Sharky – twice! – they crept into the house.

Daddy was sleeping. Daddy was sleeping so that he could begin his new job that night when he started night shift. Wasn’t that strange, she had prepared the children. Wasn’t that exciting that Daddy was going to start a new job which meant that as they were going to bed, he was going to work!

Poor Pappie, Sylvia had cried out. Poor Pappie, working in the dark. What would he see but blackness? What would he do but stumble around in the scary darkness when the world was scary and black? She would be scared. She would need to hold on to Teddy and to Golly for dear life and stay warm and snug in her bed. Would she ever have to go on night ships?

Night shift! Pieter threw himself about laughing, holding his sides in a parody of mirth. Shelley prodded him as though he were a small but fairly agreeable animal.

Grow up, she said in that adult way eleven-year-old girls have. Shelley nudged him with her bare foot that had been carefully dried.

Pieter continued to roll around on the kitchen floor, holding his sides, oinking like a little brown pig. His towel came loose to reveal his slender body all muscle and bone.

Grow up, said Shelley again, appealing to her mother to step in.

Night ships, said Sylvia again, provoking arbitration. Her thumb was dangerously close to finding its way into her mouth, despite all their talk of the New Year and Revolutions.

Resolutions, Janet said automatically.

Night ships, countered Sylvia, and then they were all at it again, killing themselves laughing. Children could be brutal little beings; Janet tried to smile at their hilarity. So much energy. So chaotic. So much life and vim and vigour. Sometimes just their sheer energy exhausted her. They drained her like a glass of milk drunk fresh and cold so that all that was left was the hint of condensation on the glass and an ache in the brain from the cold, cold milk.

Would you like some milk, she asked.

Sometimes changing the subject was best. She had become rather adept at changing the subject.

They clamoured around her, including Shelley, for the milk, which she poured into identical glasses to precisely the same point. So even though they were each separated by roughly three years, she dare not distinguish between them by a fraction of a millimetre. That would unleash chaos.

They were silent now. The kitchen resounded with their quiet gulps although before she could say Marco Polo she knew that they would be at it again. Janet leaned against the old kitchen counter with its melamine surface, and savoured the quiet for a few seconds.

How their little throats pulsed with milk. It was terrifying how quickly they could demolish a large glass of icy milk. She could not bear the sterile taste of thick milk, all white and blank. It was like drinking maternal oblivion, a liquid migraine. She wondered if Noreen next door drank too much milk. That would explain things.

Janet tried to explain things. Again. Before they finished their milk.

Remember to be quiet now, she said as their little throats throbbed. Daddy needs his sleep today. Especially today.

Three pairs of eyes watched her around upended glasses. The dregs were being drained. Every last white drop.

I won, said Pieter thumping down his glass so that Janet jumped.

Pieter! scolded Shelley, her rebuke more shrill than the solid crash of his glass.

Shhhh! hissed Sylvia louder than them both.

Janet gripped the towel she had taken from her younger daughter and tightened it around her own belly. Being a mother in a wet dress with knotted brown hair did not help matters. She felt as though she should be on holiday, on the beach, carefree. Not in a wet dress, in the kitchen, playing referee.

Children, her voice snapped like a towel flicked at their damp legs. We are all to be very quiet until two pee em. That’s what Daddy asked. Remember. That is expressly why we have spent the day around the pool. We could make a noise around the pool, but –

It is three pee em – Shelley pointed to the kitchen clock.

Pieter leapt in immediately. When the big hand is on the twelve and the small hand –

Pappie! yelled Sylvia –

Janet pressed a hand to her head. Even though she had drunk not a drop of milk. An hour, an entire hour had disappeared, simply slipped through some crack in the day. She could not stop trying to forget about the crack.

Yes, they could all run down the long passage to Mommy and Daddy’s bedroom. Yes, go on. Each one of them could charge down to the far end of the house to Daddy and wake him up. He would be cross that they had not woken him up earlier, at two pee em like he said but it could not be helped when you were left in charge of the children, all three of them, for the entire day. Maybe not the entire day, granted, but for a major portion of their waking day. There is just so much Marco Polo and Sharky that one could tolerate before beginning to lose a grip. And the sheer volume of milk that they could drink so enthusiastically –

Janet sighed.

She could hear the rumble of Hektor-Jan down the far end of the house. He sounded fine. One never knew how he might take things. How today, on New Year’s Day, after a Rip van Winkle sleep, he might take being awoken an hour late by his chlorinated and slightly sunburnt children. How would he respond if he sensed that they were crammed with cold milk. Never mind what he would do when confronted by the news of the crack. Janet wondered if she could bear to start the year with a crack. And Hektor-Jan beginning his job, no longer in the smart certainty of his uniform, but going undercover. It would have to wait. She had learned that some things would have to wait. Not all things, but some things. Mostly her things. But such is marriage. Such is marriage to a man going undercover. Also, marriage to a man who had come to live in her father’s house – which was now hers. And when such a strong man has not built his own house, but lives with his wife and family in a house that his father-in-law paid to have built, then such a marriage might seem uneven, strangely lopsided perhaps. Especially when the husband is a policeman and, unlike the father-in-law, is indeed the law. So to keep the scales of justice finely balanced, she might be inclined to acquiesce too readily, to set her things to one side, to make her man seem strong, to help him to belong.

Janet put on her bright, strong face and strolled down the passage like a woman without a crack in the world. It would have to wait. Surely, it could wait –

Mommy! Sylvia yelled from behind her father as silly Mommy entered the bedroom. Silly Mommy, she announced to the bedroom like the blast of royal fanfare.

What now, her father asked. With mock agitation furrowed in his deep Afrikaans accent.

Hektor-Jan lay in state, propped up on one elbow, his children clustered around him like loyal subjects. The thick curtains dimmed the air, took the sting out of the sun, created a deep pocket in the robe of the house. For a moment Janet thought that her sunglasses had slipped from the top of her head where, magically, they still perched. The children were shadows; Hektor-Jan was a rasping mound of manliness created out of the new duvet, which in turn was a Christma

s present to themselves. The air was thick with the fug of her husband’s warm body. Janet could scarcely breathe and she inhaled deeply.

You have been for a swim, they tell me, Hektor-Jan’s amusement radiated from the bed. Janet had to blink. After the brilliant sun and the bright milk, her eyes were struggling to adjust. She removed the sunglasses from her head and stood there obediently.

More or less, she said.

His voice rumbled from the depths of his children. More or less of a swim, he waved a meaty hand. You’re soaking wet.

Janet removed the towel from her waist self-consciously. She turned her head and her back and coiled her hair in the towel, twisting it so that more water was squeezed from her hair. But she could feel drips trickling down her legs. Running in little rivulets, still, and spotting the carpet. If that were the children, she would have a fit. They would be despatched from the house with a curt Will you go and get yourself dry for goodness’ sake – how many times must I tell you. Whereas Hektor-Jan urinated standing up and there was no way that she could dismiss him from his own loo with such sudden commands as she mopped up. There were some things one could not leave for Alice even though she was a live-in maid and was paid to clean up after them and had no doubt faced worse challenges in her life. How men could urinate standing up was beyond her: the abandon, the carelessness, the masculine effrontery. It distressed her more than most things and she pressed her lips together.

Janet squeezed and squeezed her hair and glanced in the dressing-table mirror hoping that Hektor-Jan would not notice the hypocritical drops of water that dotted the beige carpet.

He was wrestling with the children now.

She squeezed until her head hurt and the towel was sodden.

Hektor-Jan and Shelley and Pieter and Sylvia were a tangle of dusky limbs and loud grunts. They were trying to pin his arms down so that they could tickle him. But one hand kept escaping and sneaking around to push them off balance so that they fell against him and he could tickle them. Pappie, they cried. Pappie, they chortled and gurgled and were throttled with excited gasps. They were like one sixteen-limbed creature in the bed. The new duvet was in turmoil; she should never have bothered to iron the cover. Still, Alice would soon be back. And the bizarre, eight-legged human spider thrashed and squealed like an effeminate ventriloquist until one of them would knee Hektor-Jan in the privates. Then his voice would split the dark with a roar. But it was a mock-roar, half pain, half game.

The Crack

The Crack