- Home

- Christopher Radmann

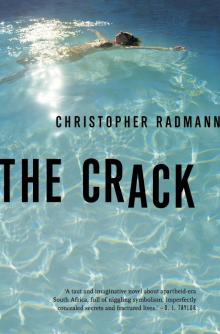

The Crack

The Crack Read online

1mm

The Soweto Uprising, 1976

At about 7 a.m. on 16 June 1976, thousands of African school students in Soweto gathered at prearranged assembly points for a demonstration. They launched a movement that began in opposition to the imposition of Afrikaans as a medium of instruction (in African schools), and developed, over twenty months, into a countrywide youth uprising against the apartheid regime.

This movement cost the lives of more than a thousand youths. But, like an earthquake, it opened up a huge fissure in South African history, separating one era from another. It politicised a whole new generation of youth, and consigned beyond recall the era of defeats in the 1960s. It announced the determination of the youth to end one of the most barbaric examples of modern capitalist slavery.

– Weizmann Hamilton writing in Inqaba Ya Basebenzi (Fortress of the Revolution)

The police garage was next to the mortuary, and the bodies of soldiers who had died in police or army operations came in daily. We began to keep score. I soon got used to the idea that a human life had very little value.

– Johan Marais, Time Bomb: A Policeman’s True Story

The crack appeared at the bottom of the swimming pool on 1 January 1976.

Or, possibly more accurately, it was on 1 January 1976 that Janet first noticed the crack at the bottom of the swimming pool.

It was not a big crack as far as cracks go. In fact, it went nowhere. It simply shimmered beneath the wobbling water as her three children lay on the slasto at the pool’s edge. Did she even see it.

The children lay panting and glistening like oiled seals in the midsummer sun. Beads of water sparkled on their brown backs. Even from behind her sunglasses, Janet’s eyes winced at the brightness of their silvery-brown skin. They lay recovering from a game of Marco Polo that had descended into Sharky and the swallowing of great gasps of chlorinated water by the boy in the middle.

Janet had come across from her deep oasis beneath the willow tree, summoned from her uncomfortable doze by the sounds of Pieter’s sisters berating his attempts at drowning. Her haven, a heaven of soft-lime striations, had yielded to their impetuous squeals. She had burst through the shroud of branches straight into the light.

Sis, man, the girls shrieked in that high-tensile, female way.

Ag, sis, man.

Ma, Ma, look at Pieter.

Their shrill cries had hooked her out of the limbo into which she was sinking. Into which she had been sinking these last eleven years. One moment she was drifting into the haze of steaming pine scent that seeped across from the neighbour’s garden. Then she was on her feet and moving fast across the big lawn as Pieter spewed his lunch over the side of the pool.

She was in time to see the carrots she had chopped so finely lend a colourful sheen to the slasto beside the pool. Offset by the red and white of the radishes.

Gross, man, Pieter’s sisters screamed with the addition of gagging sounds.

Gross, squealed the older.

That’s quite enough, Shelley, she snapped.

Gross, echoed the younger.

Be quiet, Sylvia, her mouth opened and slammed shut.

Pieter knelt at her feet like a dog. Or a piggy, in the middle of two very vocal sisters. He seemed to be studying his reconfigured lunch with some surprise. He raised a hand and for a moment his mother wondered whether he was going to poke it, to play with his food that shone in the viscous sun, neatly filling the cracks in the crazy paving. Instead, he wiped his mouth and raised his little face to her.

Sorry, Mommy, he said.

I said that you should not go mad in the pool after lunch.

His face fell.

She was scolding herself, for letting them go berserk so soon after eating, but his little face fell.

All their faces fell.

It wasn’t the vomit that was ruining their game. It was her sharp voice. Her voice that cut through their childish fun and frolics. So what if Marco Polo had discovered the skill of projectile vomiting. Who really cared if Sharky now surfed through an acidic salad. Her sharp voice had snipped off the fringe of their fun and games. They were silly children now. Shelley. Pieter. And Sylvia. Three blonde heads and lithe bodies. Perfect little bodies gathered around the sick at the side of the pool.

She gave commands.

All shrieking stopped and they began to splash water from the pool so that it gushed over the vomit and sent it coursing to the edge of the slasto and onto the grass. The little bits of carrot, radish and lettuce lay wilting in the ferocious sun. Of the thick slices of wholemeal bread, oddly, there seemed no trace.

Then they moved off to one side where the slasto was lovely and hot, and lay panting and glistening like oiled seals in the midsummer sun. Beads of water sparkled on their brown backs. Even from behind her sunglasses, Janet’s eyes winced at the brightness of their silvery-brown skin. Then her eyes were drawn to the wobbling water that lassoed the sun into strange rings and coils. And there, beneath it all, was the crack.

For a moment, she thought that there was no crack. Surely if there were a crack, the water level would have dipped. Surely, she would have noticed if the water level had dipped. Or Solomon would have said something about the water level dropping. Nothing had been said or noticed. Until now.

She stood there. Her three little silver darlings shivered in the heat and murmured to one side. She slid her sunglasses onto the top of her head. She stood over the pool, leaning out as far as she dared. Still the water looped and coiled the glinting light. It would take time for the waves to settle.

But she had time.

Of that commodity she had an abundance.

Always that sense of time on her hands. As though time were some sticky substance that clung to her fingers and had to be carefully scoured off. Rubbed off with care and Sunlight soap so that it did not stick under her wedding ring or catch in the gap between the white gold of that ring and its little neighbour – the more recent eternity ring presented to her by Hektor-Jan after the birth of their third child, precious little Sylvia. Well done, said the ring. Well done on securing the next generation of white South African children, but enough, now, no more. The future is safe as the eternal circle of the ring suggests, but enough, too, as the white gold zero urgently implies. For ever and now. It felt strange accepting, for a second time, such a ring from such a man. Everything and nothing.

Janet found herself looking down at her hands that rubbed themselves all the time in a silent ritual even though there was no sticky substance that clung to her skin. She quietly folded her arms and stood there, looking down. Trying to peer through the azure gleam of the water, like a priestess trying to divine the heavens. Yet in Janet’s case, her lips thinned as she smiled a tight smile, the heavens were an 8 × 5 metre swimming pool that reeked of chlorine and responsibility and was stuck at the far end of a suburban garden in the heart of the East Rand, in the town, Benoni, on this, the first day of another new year, 1976.

She waited for the waves to subside. They must eventually settle down to a flat rectangle of blue that would present the world with one hot sun on its calm surface. And then she could move along the edge of the pool and find a spot that did not blind her, and then she could see to the bottom of the pool. She could see where the leaves lurked. Where moths and grasshoppers lay in the sapphire depths dreaming that they were flying free instead of being suspended in their 8 x 5 metre liquid tomb and going nowhere. Nowhere but up the coiled length of the Kreepy Krauly that would switch on at night and go chugging around the pool sucking up the leaves and the little dead bodies. Janet would lie awake and listen to the heartbeat coming from the swimming pool at the other end of the long garden. Sometimes it sounded like Hektor-Jan’s heartbeat or her own, bu

t she knew that the timer had clicked and that the new Kreepy Krauly had begun its circuit of precisely random cleaning of the pool. That as they slept through the insistent chirping of crickets and the howl of a hunting mosquito, the little bodies at the bottom of the pool would disappear up the jerking, pulsing funnel of the Kreepy Krauly. In the morning, they would be gone, all those foetal corpses, and the pool would be ready for another day: fresh, blank and blue. It was the opposite of birth. It was a beautiful obliteration.

But now there was the crack.

Somewhere.

Somewhere beneath the mass of shifting water she had seen, had sensed possibly, the crack. Janet almost wondered whether it was that that had awoken her in the early hours between 1975 and 1976. Whether she had, in fact, heard the smooth concrete split and had murmured in her half-awake, half-asleep dwaal. Murmured to Hektor-Jan that there was something out there.

But she couldn’t have murmured anything. Certainly Hektor-Jan could not have heard anything, as he would have been up like a shot, switching on the emergency torch and getting the gun and leaving his wife gasping.

You never mess around with things like that, he would have said. Better to be safe than sorry. And he would have gone prowling through the deep house with his torch and his gun. Checking doors and windows. Ready to defend hearth and home. And the children would have been noisily sleeping in that messy way children have, she prayed. All snores and snufflings, please, dear God. Pieter in his own little room and Shelley and Sylvia together in theirs. Please, oh please. And every lock and burglar bar would be safe and secure and the children still squirming from the excesses of Christmas and not yet ready for school. He would wander to the spare bedroom, the one that looked out over the little courtyard to the maid’s quarters, the kaya that abutted the double garage, and check that there were no comings and goings there. Janet held her breath. Then Hektor-Jan would have returned with his hand over his torch so as not to blind her and would have hidden his gun. With a playful slap where her nightie just about covered her bottom, he would sink into bed and perhaps into her again as she lay in fear of what might have been out there. Hektor-Jan would try to continue celebrating the start of the new year in style. They had had a busy night of it. They had gone round for drinks at the neighbours to their left, but then straight home and to bed for the children, who would be starting school in a week’s time. The playful slap after the playful clinking of glasses to usher in 1976. It was going to be a good one. To continue the economic recovery after the grim times. That’s what Doug had said as he raised yet another glass of 5th Avenue Cold Duck sparkling wine and refilled theirs and Noreen had quacked away with flushed cheeks and they had all said, Cheers! once more. And Hektor-Jan had made a lovely speech. Surprising, impromptu, but a sweet speech. Yes, 1976 was set to be a good one.

And just before the stroke of midnight, after they had returned home and put the murmuring children to bed, she and Hektor-Jan had escaped from the house into the cool depths of the garden. And bubbling after the third bottle of 5th Avenue Cold Duck, they had giggled their clothes to the ground and slipped into the coolness of the pool. When last had they skinny-dipped. When last had Hektor-Jan been free of his uniform, and Janet so uninhibited. The booze made them brave. The chlorinated water made their skin hard and Janet had said Goodness me, it was happening so unexpectedly and Hektor-Jan had whispered Happy New Year and had made another pass at her. But there was moonlight and the black water shone very brightly and Hektor-Jan had said The children – and Janet had remembered and she had playfully pulled him. Out of the pool she pulled him and he could not resist as 1975 slipped aside and in flooded 1976. They kissed beside the pampas grass. They kissed beneath the willow tree, but the moonlight was bright and the windows of the house were watchful. They were alone, but the children – the children. So Hektor-Jan bent his strong arms and she was lifted as light as a fluted glass brimming with bubbles and, like the sparkling wine, she was swept off her feet to the side of the house. Shhh, breathed Hektor-Jan as she chuckled and tried not to snort in an unladylike way, and then they were at the double garage which adjoined the maid’s quarters, but Alice was not back yet. And Hektor-Jan wiggled his eyebrows in the moonlight and before she knew it they were in the garage and there was the smell of oil and paint and soft sawdust. The concrete floor was cold as he let her down slowly, slowly down the length of his burly body. And her husband was warm and he turned her and she leaned on the smooth metal of the parked car and Hektor-Jan took charge from behind. But then you could not tell who was leading and who was following as they struggled together over the cold bonnet of the Fiat – which had the habit of backfiring. Janet almost heard the car as Hektor-Jan crashed behind her. There was a warm bang, the gasp of a sound as something metal fell, some big tool, and then it was just their laughter as she bucked and called, Hektor, my Hektor-Jan, and Hektor-Jan cried, Janet, Janet, right beside her ear. And all her senses were arrested as her policeman husband held her, overwhelmed her, with his great love. And then she turned and kissed him.

They were so close. Locked together in the oily garage with their wet skin and warm kisses. Gentle and rough, loud and quiet.

That was 1975. Or was it 1976.

It will be different, he whispered. New. A brave new year.

And now, already, the crack. Tomorrow, next year, was already today. And it was the first of January – definitely a very bright, new day –

Still the water wobbled. But the many, many suns were slowly reducing in number. It would not be long before the water lay calm and yielded up the bottom of the pool. And Janet had time. Great, generous dollops of sticky time.

Alice would be back soon. Helping to clear up the mess as all that time melted and dripped through her fingers. Ah, the luxury of a live-in maid. So many in white South Africa had a live-in maid. What was life without a black live-in maid. Her Alice. Who helped her to make and preserve a wonderland.

Last night Noreen had gone on about life without her girl, her Emily. About the mysterious pregnancy, as Emily was not supposed to have gentlemen callers while she was there in the kaya working for them full time. Her Emily had given notice and Doug and Noreen were looking for a new maid. Emily had gone back to Daveyton, the sprawling township a train-ride away from Benoni, and from there back to Zululand, apparently. Now they were looking for a new maid. And Janet had tried not to let Hektor-Jan’s hand on her shoulder distract her – his fingers were the size of fists – while Noreen asked, Did Janet’s Alice know anyone. Or Alice’s mother, the old but legendary Lettie. Surely she would know someone, or have another daughter or niece or whatever who needed work.

Her Alice, Janet was sure, would know several young women keen to escape into a kaya that lay adjoined to the back of a double garage. A neat retreat from life in the townships of the East Rand. To be yoked to a white family from morning until night with the odd afternoon off. To be spared the multifarious claims of one’s own family by being pressed into service of another family and paid for it. To become a domestic servant. To suspend yourself in domestic servitude until the Kreepy Krauly of life sucked you up and out. Isn’t that what happened to Noreen’s Emily. Her womb, like the pulsing funnel of the Kreepy Krauly, had sucked her up and out of her old way of life. Now she was gone. Their pool was clean. Clean, but somehow bare. Noreen had said, That was one way of looking at it, yes, for sure, if you put it like that, and Hektor-Jan had secretly pinched Janet softly on the bottom, just there, right where her bottom began.

And there was the crack on this, the bold, blue 1 January 1976. In the heart of the swimming pool and running along its entire length. A hairline fracture in the concrete scalp of the pool. Not much to look at. Indeed, barely noticed. In fact, completely unnoticed were it not for the game of Marco Polo followed rather too soon by Sharky and Pieter’s vomiting.

Janet stood with her arms folded, looking down. She could be a bird in the sky, looking down from the heavens on the world far below. Perceiving some divine

st sense – to a discerning eye, or perhaps amazing sense – from ordinary meanings. Her delicate hands lay resting on her arms. They were her wings, and folded, so she did not fly and she could not be a bird. Then she unfolded her arms and knelt down at the edge of the pool for an even closer look. Maybe she was a giraffe now, her limbs splayed out to support her weight as she peered over the edge of the pool, straining ever further to see what was shimmering there at the bottom of the pool. She bit her lip. It was a crack, of that there was no doubt. Why had the children not said. They played in the pool incessantly. It was their second home. Why had Solomon the gardener not said. He basically lived in the garden, both in the front and the back garden. Surely someone should have noticed and raised the alarm. Come running to her to say Mommy or Madam, there is a crack at the bottom of the pool in this the year of our Lord, 1976. The children should have called Mommy! And Solomon could have spoken softly, his shaven head respectfully bowed as he clutched his rake for support and said, Madam, the swimming pool, eish.

She did not need this in her life. Not at this juncture. Not with Hektor-Jan about to start working a new shift and certainly not with the play that they hoped to put on, the great drama scheduled for the end of the summer. They had only a few months.

Maybe it would go away.

Janet stood there on the edge of the pool.

She could feel the house in the background, squatting prettily within the newish cement-slab walls that bounded the property and already hidden by big, established shrubs. She felt the fierce green grass, the lawn that seethed from the house all the way to the pool at the far end of the garden. And she could feel the shrubs and trees and flowers and insects all buzzing and bursting in the midsummer sun. Everything that kept Solomon busy like a ragged black bee three days a week whilst Doug and Noreen next door had him only for two. And the unexplained absence of Wednesdays, the gap in the middle of the week when who knows where Solomon went. The bee, the bee is not afraid of me, she thought as she tried to swat away the humming sound that persisted on the edge of sense.

The Crack

The Crack