- Home

- Christopher Radmann

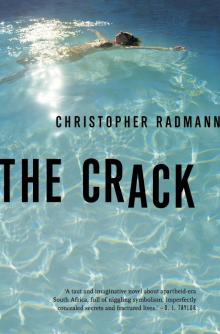

The Crack Page 9

The Crack Read online

Page 9

Shelley’s Secret Journal

Word for the day from Granny’s list is INVIOLABLE

Pieter’s face is not inviolable. Dogs are not inviolable. I hope moles are either inviolable or quickly violable. Mommy was creeping around the garden last night. What is she looking for? Jock is buried and will become part of the soil, flowers and so on till he is almost inviolable. Pieter and Sylvia and I do not like it when they lock the bedroom door to have sex although the little ones do not know about sex yet. Granny you have not told them yet and I have kept my promise not to tell Pieter or Sylvia. Granny you called it the sex act. Mommy is going to act in a musical. I have to act like I don’t know what is going on. Sometimes I wish I had not seen what happened to Jock and I don’t like to think about the sex act either. Even if you said indubitably it makes you feel inviolable. Granny try not to eat any more tissues. Love, Shelley.

3.2cm

Allied to the blacks’ appalling conditions in both town and country, the constant harassment by police and the consciousness of political and social paralysis, the inevitability of violence was stark. Three weeks before the [Sowetan Uprising] massacre the Anglican Bishop of Johannesburg, Desmond Tutu, who was emerging as one of the most influential black leaders, had written an open letter to [State President] Vorster expressing his ‘nightmarish fear that unless something drastic is done very soon, then bloodshed and violence are going to happen … almost inevitably … A people made desperate by despair and injustice and oppression will use desperate means.’

– Frank Welsh, A History of South Africa, Chapter 18: Disintegration

The Poor Man

Pity the poor man buried in white skin.

There is nothing thicker, more weighty than white skin.

Just like steel-reinforced concrete and armour plating and bullet-proof glass,

Nothing seems to penetrate such a tough carapace.

Neither guilt, remorse nor the pangs of conscience.

The poor man must carry it with him to confession,

Drag it about the city streets, lug it along the corridors of power.

How it must distend and distort his face as he peers in the mirror.

No, there is nothing thicker, more weighty, than white, white skin.

– Abraham Nkosi

Indeed, it was a long weekend. But, at the end of it, Alice did return.

It was Sunday afternoon.

Hektor-Jan was out the front, fiddling with the car and waited on hand and foot by his faithful Pieter and watched by Sylvia of the piercing voice and disquieting perceptions. Shelley was somewhere inside, reading no doubt.

The back garden was a haze of thick, aromatic scent. Invisibly, it poured from the giant pine next door and seemed to fill the garden from wall to wall in the hot, still air. The garden filled like a pool, filled with thick liquid scent and Janet sank into it, drowning happily.

Janet lay under the willow tree.

Her script, dangled limply from her hand, slowly licked up the sweat which trickled from her fingers. The mists of Brigadoon soaked up the sweat pulled from her pores by the heat of Benoni.

Once in a hundred years, the magical town of Brigadoon would appear, intact and inviolable. Out of the Highland mists it would come, an enchanted place, a hallowed place. Forever free from the threat of disruption or change. Quaint customs were eternally preserved and the villagers sang of home and bonnie Jean. Here there was no crack. Janet could hardly wait for the first rehearsal. To leave the merciless blue of the Highveld sky and enter the more maternal mists of the Scottish Highlands. To set aside Janet for a few hours and to become the celebrated and vivacious bonnie Jean. To sing and be sung to, and to dance. Hektor-Jan did not dance. He did a lot of things, but he did not dance.

He had taken the children off to kerk that morning. All dressed in their Sunday best. Hektor-Jan in his suit which fitted him like a leash, which held back the power and strength of his square body, just about containing his big muscles and thick neck. He looked ready to explode and he ran a blunt finger under his collar. Too much of the good life, he muttered as his children were assembled before him. Janet watched him straighten his tie, which bulged in a dark line over his chest and stomach.

The children were finally ready.

Janet had fielded with absent-minded equanimity the weekly questions.

Why was she allowed to stay at home? Why did they have to go? Kerk is boring, Mommy. Can someone die of boredom? They have come close to death by boredom every week. Dominee speaks funny, Mommy. He shakes his fist at me, Mommy, and when he reads from Die Bybel, his voice starts to shake and we can see his spit. It collects in the corners of his mouth, it really does. I swear it does. When the sun comes in the back window I can see the dust in the air, Mommy: it’s like he is swimming in all the dust in the air, like it is pouring down on him and he spits. We can see the spit flying out of his mouth into the shining dust. It almost gets us, Mommy. One day it’s going to hit us, isn’t it, Shelley? Didn’t you get some on your cheek last week? You said you got some on your cheek last week. I got some on my cheek. I am not a liar, you said you got some –

And when they were gone in the throb of a freshly tuned Ford Cortina, Janet would remain standing on the pavement, a small figure beside the line of plane trees that ran down the length of the road. Her hand would be raised in a motherly salute. Or perhaps it was a gesture of submission or maybe even of protest. After a few moments, she would look up at her hand, as though wondering who had set it there at such an angle above her head. And she would bring it down, bring it back down to hang at her side as she turned and made her way into the silent house. Usually, she would leave the beds and the breakfast things for Alice to tidy up before Alice, too, would head off for the rest of the day to her church events and whatever she did on a Sunday afternoon in an East Rand suburb.

And then Janet, tingling with pleasurable anticipation, would walk slowly to the lounge. She would walk across to her favourite piece of furniture, her childhood, it seemed, memorialised in glowing wood and perched on four beautifully curved short legs, each culminating in a wonderfully orbed, clawed foot. It was like having a lion in the lounge, an Aslan in smooth, honeyed wood all gleaming and shining from Alice’s devoted polishing. There it stood, wreathed in the soft flames of the morning sunshine that streamed into the north-facing house. The radiogram.

Janet would make sure that it was switched on, and then she would gently open the pair of doors which glided down to bring with them the record player on the one side and the dials and volume knobs and radio-station tuner on the other side. Then she found her favourite record in the neat drawer at the top of the radiogram. And before long, the black wheel, the glossy whirlpool of the LP began to spin, began to rotate and the grooves which contained all the wonderful music lilted up and down almost sinuously. Janet might watch those many, many lines spin with promise as the record undulated before her eyes and the subtle hiss came from the speakers. Then, finally, unable to resist the pleasure any longer, Janet raised the white arm with the hooked needle and gently lowered it onto the outer edge of the record. It might hesitate for a tiny second, but then it caught a groove and took. And Janet would step back as though in a dream, and feel her way to the low couch onto which she would sink as the liquid, clear and mellow voice of Karen Carpenter filled the room.

Alone, she could have the volume as loud as she liked, and she liked it loud. With her children and their father neatly seated in the dusty kerk before the spitting Dominee, Janet could sink into golden sounds of the Carpenters that glowed in the sunlight and filled her with such feeling. (They Long to be) Close to You and We’ve Only Just Begun washed over her. Please Mr Postman and Love is Surrender called to her soul and she moved her lips to the lyrics of As Time Goes By and Only Yesterday before singing along to The Night Has a Thousand Eyes, Desperado and Solitaire., For several hours, LP after LP, Janet could be swept along by the beautiful harmonising of the sister and

brother. It was the call of the woman with the hair the same colour as Janet’s but the voice and the looks of an angel, so thin and so delicate, that tugged at her heartstrings and let her weep with joy.

But that morning she had to search the house for her script. No Karen or Richard Carpenter for her. No time spent crooning on the couch.

She had to find her words. Brigadoon did not just vanish in the mists of Scotland, it seemed. How often did she have to hunt it down in her own home. Very strange. She wondered if the rest of the merry cast had the same problem. She tried not to think about her mother’s dementia, how it started with the little things. Spectacles lost on the top of her head. The tasty tissues. Starting to go to the loo in the lounge. Attacking her own grandson. And all those other things from long ago. Too many things from long ago. Janet would rush from the house with the relieved and gasping script clutched firmly in her hand and sink back with a shudder under the willow tree. This was a profound sacrifice. To forsake Karen Carpenter for the script of Brigadoon was a terrible sacrifice indeed.

Before she plunged in, Janet lay back and marvelled again at the tree whose branches knew to grow to a precise length, just long enough to arc from the main branches above, and to cascade down to kiss the ground. No branch grew too long. Whatever the fall of each frond, it did not go too far to lie wastefully on the ground. No, each tip stopped just short, or merely touched the ground. Janet lay back, overwhelmed by such chaotic precision. The tangled order, the cluttered symmetry of the tree shrouded her and she raised the damp script of Brigadoon to her eyes that stared up at the mesmerising, living lines above her.

Then it was at least an hour of focusing on the printed page. Making sure that those lines now started to fill her head. Janet could be pushed a little to one side. The clamour of domestic duties and insistent children who feared death by boredom and the dangers of excessively expectorant dominees could be set to one side. Janet could become Jean. And bonnie Jean to boot. In her mind’s eye, she danced gracefully on stage. Ready for every cue, she responded with quick and fluid timing. No longueurs, no ghastly gaps whilst the audience stared embarrassed and the whole show fell apart. Oh no. They were too good for that. They might be an amateur dramatic society on the East Rand, but they had their pride.

And as a little reward, after at least two-dozen lines were learnt, Janet might slip from her brown and lime bower and into her favourite bikini. Then she would grab a swimming towel and drag the old lounger from beneath the tree and she would lie in the morning sun. It was hot but not too frazzling. Bonnie Jean would soak up the Benoni sun. And as she went through the lines, now a shifting set of words and emotions in her mind, she might be aware on the edge, on the periphery of consciousness, of the rustle of the rhododendrons or even the glint from somewhere in their neighbourly depths of a pair of cautious binoculars. Usually the children would tell her. Sidle up to her and whisper, Uncle Doug is at it again. Except on Sundays, when there were no children and Doug could spy away with impunity.

Janet wondered whether she should make a scene. She was half-conscious of the irony that here she was, preparing to expose herself on stage, to be viewed by a school hall of watching eyes, and the fact that she might be a little squeamish about a neighbour – a good friend – admiring her from the very depths of his rhododendrons. He was just one set of eyes. But then she thought of the glinting binoculars, the power-assisted scrutiny. Part of her wondered how close Doug got. What part of her filled his secret vision. Then did she become angry on Noreen’s behalf. Did she feel some feminist revulsion, some outrage at a not-so-subtle form of male exploitation or implicit degradation. Or was she somehow flattered that her body, which had yielded up three children and was preparing to launch a fourth, could still arouse male interest. After all, was that not the very reason she loved the idea of performing on stage. To be noticed. To be applauded. Were Doug’s frequent fumblings in the foliage not simply a rather welcome form of applause.

She lay there with the sun stinging her skin.

That was simpler. To forget about the complexities of motive and morality. Probably preferable to let the sun bleach those dark thoughts. To render them translucent and gleaming and white. Leached of all insidious intent. Just thoughts. She was here. He was there. The sun was hot. The sun stung her skin with beautiful heat. Doug was their neighbour. He liked looking at her. Life could be simple. Life could be brilliantly clear and simple. Indeed, the sun was hot.

And out of the blinding heat, Alice came home. It seemed as though the white sun and the vast sky had finally yielded her up. There was the metal squeal of the side door that led from the alleyway between the garage and the house, from the front garden to the back. Out of the Sunday morning there was the shriek of iron as though the sun had sheared off a slice of the day, and there was Alice. Alice in her beautiful Jet Store – or Edgars – outfit. Chic and smiling and waiting to greet her Madam, who lay as though murdered by the sun.

After all this time, and Janet did not seem to register Alice’s return. The rhododendrons twitched in her mind and the sun sang. The day seemed to creak metallically and a dark shadow appeared. Janet lay dead still. Then she lifted her head and peered behind her.

Alice!

Janet sprang from her towel with touching abandon, like a child forgetful of propriety in the enthusiasm to greet its Alice.

Alice!

She stood before Alice, her skin silver with a film of sweat that sparkled in the sun. And Alice smiled at her.

Janet laughed, now suddenly aware of her tight bikini, of the possibly startling conjunction of maternal curves barely captured by little triangles of bright cloth.

Alice! she said, laughing and raising a hand to her mouth. Alice, we were so worried. We wondered what happened. We thought you were coming back on Friday. Is everything all right. Nothing went wrong.

Alice lowered her two big bags to the ground. She rubbed her hands and then placed them on her hips. She was a tall woman, statuesque. She was dressed in the latest fashion and her hair was set free – swept away from her face and clipped at the back. Her lipstick was a beautiful plum and now her teeth gleamed as she smiled.

Here I am, she said. She spoke such good English, clear and precise, although her accent had not managed to break free of the townships. Heh I em, she said – music to Janet’s ears.

Thank goodness, said Janet. We were so worried; I was so worried.

Busy, busy, busy, said Alice, her favourite and most familiar phrase. Then the taxi – eish. She shook her head.

Janet could only imagine. The crowded minibus taxi, stuffed to the rafters, packed like sardines.

Ja, said Alice. The minibus taxi broke down. They had to wait at the side of the road for the whole day, and then they had to sleep in the taxi. Hau, it was bad, very much too bad. A catastrophe. She aired that word with a gleam of her impossible teeth.

Janet shook her head.

I am so glad that you are back safe and sound, she said. The children will be delighted. They are at –

Kerk, said Alice.

And Janet nodded. It is just us, she said. Go and unpack, she said, not quite yet the white Madam. Go and unpack and I’ll make us a nice cup of tea.

Alice looked once more around the garden. Set Janet carefully in the context of the unkempt lawn that leapt up to demand attention, set her against the backdrop of weeping willow and lounger that lay stunned in the sun. And there was the bright brickwork of the garage and the adjoining kaya, and then beyond that the neighbour’s wall and the profusion of pampas hiding the compost mound and the small vegetable garden. Then the back wall and the pool and the neighbours to their right as they faced the back garden. There were signs of the children too. The chaotic hosepipe, no doubt stuffed down a mole hole, the brown leather rugby ball and the pair of hula hoops. But no little landmines left by Jock. No, Jock lay buried in his own patch behind the pampas grass with a tiny, troubled cross fashioned by small hands. That was December; this was January. And th

e crack. If Alice sensed the crack she gave no sign at all. And Janet took one of Alice’s hands in her own and gave it a squeeze. Welcome home.

So this was home.

They had finished their tea and Janet had told Alice all about Brigadoon by the time the children returned. Alice was back in her maid’s outfit, her pink shift, apron and doek and standing doing the dishes when the children burst in, freed for another week from the hell of kerk.

Alice! they shrieked in triplicate surprise and joy. Alice! and they ran helter-skelter to her and engulfed her with hugs and squeals. And Janet smiled as Alice hugged them back, clasped them to her, her little white brood, so smart in their Sunday best that their father made them wear. The children so smart and Alice so maternal and pink in her familiar uniform as it were.

The Crack

The Crack